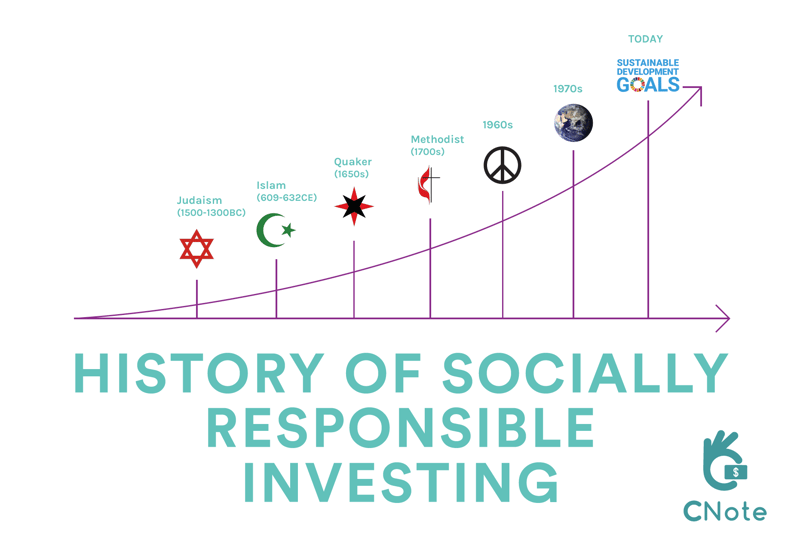

The history of SRI

The earliest precursors of socially responsible investing date back to the Pentateuch – the first five books of the Bible, believed to have been written by Moses as early as 1500 BC. The books refer to a Jewish concept called Tzedek (justice and equity) and how it should govern all aspects of life. Tzedek aimed to correct the imbalances that humans inevitably generate, including the benefits one would receive from ownership. Owners had rights and responsibilities in how holdings were used, one of which was to prevent any immediate or potential harm.

This principle formed the genesis of socially responsible investing, providing religious and indigenous cultures with a set of criteria on how to generate financial returns ethically and sustainably.

Note: The above image provides a cursory summary of some of the movements and institutions that have shaped SRI investing as we know it today. It is not intended to be a completely exhaustive list.

Religious roots and origins of socially responsible investing

Despite a consensus that ethics were an essential consideration for investment decisions, the application of the principle varied; some groups used it as a guideline, others required it by law. The basis for SRI varies between religious groups, leading to many different interpretations of the subject.

Judaism (1500-1300BC)

As mentioned above, Judaism sees a need for justice/equity in all aspects of life, including government and economic activity. Jewish Law states that investments make us property owners, giving us the responsibility to use our holdings to prevent immediate and potential harm.

While most biblical and rabbinic sources refer to single owners or small partnerships, Jewish religious figures eventually addressed the ethics of shareholder responsibility. Since shareholding is a form of ownership, investors must consider the ethical responsibilities of a company before investing. This prevented followers from investing in “immoral” companies such as those involved in oil, coal and gas because of their immediate impact on human health.

Islam (609-632CE)

The Qur’an established guidelines surrounding investments based on the teachings of Islam, now known as Shariah-Compliant Finance. This philosophy aims to govern the relationship between risk and profit, along with the responsibilities of institutions and individuals. It states that money should be a medium of exchange, not an asset that grows over time. One of the governing principles in the Qur’an is Riba, which aims to prevent exploitation from the use of money. It prohibits the the lending of money at exorbitant interest rate as well as gambling or speculation. The Qur’an also forbids any Islamic institution or individual from investing in alcohol, pork products, immoral goods, gold & silver and weapons.

Quaker (1650s)

Based in England since the 1650s, Quakers are members of a group called The Religious Society of Friends. While the group is primarily interested in Christianity, it is also known for its opposition to slavery and war. In 1758, the Quaker Philadelphia Yearly Meeting prohibited members from participating in the slave trade, marking one of the first occurrences of SRI in its current form. Eventually, some Quakers went on to establish two of the largest financial institutions in modern history: Barclay’s and Lloyd’s.

Methodist (1700s)

Established in 1703, the Methodist movement was led by a man named John Wesley, one of the most articulate early adopters of SRI. During a sermon titled “The Use of Money”, Wesley outlined his stance on social investing; avoid industries that have the potential to harm workers and any business practices that might harm your neighbour. Followers eventually resisted investments in “sinful” companies, such as those involved in tobacco, firearms and alcohol. A prelude to modern exclusionary investment screening.

Modern Era: The rising popularity of SRI

The modern version of SRI in America really took hold in the mid 1900s, when investors began to avoid “sin” stocks – companies that dealt in alcohol, tobacco or gambling. In 1950, the Boston-based Pioneer Fund, established in 1928, doubled down on this movement, becoming one of the first funds to adopt SRI principles.

The avoidance of sin stocks in the 1950s marked the beginning of the rise of modern socially responsible investing, each decade bringing forth an influx socially concerned investors:

1960s

Socially responsible investing in the 1960s was largely driven by politics and concerns about the Vietnam War. Protestors boycotted companies that provided weapons for the war, while groups of students demanded university endowment funds no longer invest in defense contractors.

Meanwhile, civil rights, environmental and labor movements raised awareness about social, environmental and economic issues, bridging the gap between corporate and investor responsibility. In support of these movements, trade unions like the United Mine Workers and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union deployed targeted investments into medical facilities and union-built housing projects.

1970s

In April of 1970, 20 million Americans convened for the first Earth Day celebration, opening the door for a cascade of environmental and consumer protection legislation in the early 1970s. As society reacted to war, sweatshops, Apartheid, climate change, human trafficking and a number of other political and cultural issues, socially responsible investors followed suit. Supported by consistent efforts from both investors and corporations, it was clear that the SRI movement was here to stay. A growing number of new funds combined social and environmental consciousness with financial objectives, reflecting the prevalence of aspirational progressive values. The Pax World Fund and the First Spectrum Fund were established in 1971, followed by the Dreyfus Third Century Fund, firmly backed by over $25 million.

1980s

In the wake of the Bhopal, Chernobyl and Exxon Valdez disasters, concerns about the environment and climate change were at the core of SRI in the 1980s. This led to the launch of the United States Sustainable Investment Forum (SIF) in 1984, which has now become one of the largest resources for SRI and impact investing. The standardized approach to SRI in the 1980s involved building a portfolio that behaved like the traditional market while avoiding investments in alcohol, tobacco, weapons, gambling and environmental pollution. Firms paired these avoidance screens with a commitment to shareholder activism, a practice that allowed shareholders to leverage ownership to improve a company’s behavior.

1990s

By 1990, the popularity of SRI mutual funds and socially conscious investing hastened the need for a way to measure performance. Launched in 1990, The Domini Social Index (which is now the MSCI KLD 400 Social Index), was comprised of 400 U.S. publicly-traded companies that met certain social and environmental standards. Many potential investors were concerned that socially responsible investments would have lower returns than traditional investments, but this index helped to disprove those claims.

2000s and beyond

By the early 2000s, socially responsible investing continued to gain supporters, alongside the introduction of many major initiatives and funds. In 2006, the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment was launched, establishing guidelines for mainstream investors to incorporate ESG (environmental, social and governance) issues into investment practices. Many socially conscious investors are going beyond SRI to seek out investments that prioritize a positive impact, sparking a rise in ESG and impact investing. This forward-thinking approach was reinforced by the UN Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. These goals, backed by all 193 UN Member States, are an urgent call to solve the world’s most pressing development challenges.

In 2001, Kindred Credit Union (then known as Mennonite Savings and Credit Union), joined with Mennonite Mutual Aid, and Mennonite Foundation of Canada and formed Meritas Financial Inc. Meritas was devoted solely to creating and marketing SRIs that embodied Anabaptist commitments to peace and social justice, allowing investors to align their investment portfolios with their social, ethical, governance, and environmental concerns. Meritas merged with Qtrade Financial Group in 2010 to allow it to accelerate its vision and reach a greater number of Canadians. In 2017, Qtrade Canada Inc. merged with two other investment firms to form Aviso Wealth.

Further to this, Kindred also wanted to expand beyond mutual funds, and collaborated with Sustainalytics, a leading global provider of ESG and corporate governance research and ratings to investors, to review its credit policies and procedures. On January 1, 2015, Kindred implemented screening criteria for all business loans, mortgage applications, and credit reviews. In 2016, Kindred became the first financial institution in Canada to have all their GICs validated as SRI.

Conclusion

Socially responsible investments now account for over 33% (over $17T) of all assets under professional management in the US and over $3 billion dollars in Canada, and with increased interest from the millennial generation, that number is only expected to rise. Despite the involvement of large investment firms and funds, socially responsible investments are not exclusive to institutional investors. There’s a range of retail impact investment options that allow anyone to invest ethically and responsibly.

The history of socially responsible investing shows that what’s old is new again. We can see that this growing movement shows no signs of stopping, making for an even larger impact as more investors get involved.

Adapted from “The History of Socially Responsible Investing” (©2023 CNote Group Inc.)